The Universal Waters of Loss

We may indeed cease to exist upon death, but we are all connected by our love and our grief.

I miss my grandmother today.

It’s Easter Sunday, March 31, one week before she died, all those years ago. Late in the afternoon, I went searching for something I can set the lamp with the blue lightbulb on, because it’s been on the floor. I pulled out a stack of books from under my bed, dusted them off, and out fell three poems. Three poems, on three separate sheets of paper, by Nancy Robinson, my grandmother.

I did not know my grandmother, nor do I think I ever really grieved the loss of her. There have only been a handful of moments in which her absence has felt acute. I consider her occasionally, like when someone asks me about the origin of my middle name. Sometimes, when I need guidance, I whisper up to her in the ether, that pervading not-so-empty sky above. I have said, more than once, that she is my closest dead relative, and I mean that, although I’m not sure why. I have felt, more than once, that I carry not only her blood, but fragments of her spirit. If it even works that way—does it? I don’t know.

So, it is surprising when I am suddenly overcome with heavy emotion, acting at once on the burning need to paste those three separate sheets of paper over my bed, having barely read them, and without knowing what they are about. I suddenly wish, with a kind of gasping desperation, that she were here to tell me about when she wrote each of them.

When I slow down to read the first poem, it sounds like a love poem, for she has written: “through the seams of my soul // you sing to me, soften me, curl the tips of my toes.” Who has she written this about? Not my grandfather, surely, whom she split from when my mom was still a child. I wonder who she was writing to with such temderness.

What I know of my grandmother is that she was tall, a striking presence. I know that she was a no-nonsense schoolteacher with a flair for grammar and poetry, and that she sent her poetry in to journals, to try and get them published. Me too, I think, when I think of this. What I know of my grandmother is that I resemble her, or that she resembled me, in stature, and demeanor, and the way she used to hum to herself when she was lost in thought. Oh, and I also know, because of a framed photo I have of her, that she went to Australia a few years before her death, with a man named Conrad. Maybe Conrad is the man she writes to, in this love poem that I have discovered and now pasted to my wall. The following lines reveal what she loves about this person—“raindrops of intellect // that splash through your speech...the joy of your essence…” My grandmother loved to learn, this I don’t know, but am sure of. I wonder if she was the kind of woman who had a lot of questions, and whether she ever felt like she had the answers. I wonder what answers she would give to my questions. I wonder what she knew.

What I would give to know.

She ends the poem—which is called “Raindrops of Intellect”—with this: “answer my questions // and yours?”

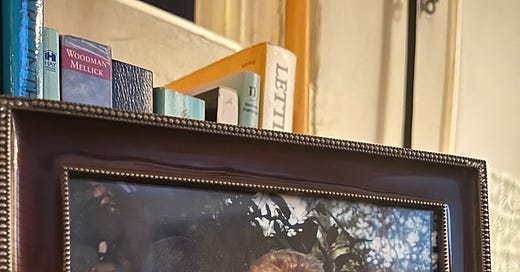

In a second wave fueled by a pressing need to do this now, I race around my room, rifling through drawers, sorting pictures as pressure builds behind my eyes. I fear I have lost it—but then I remember, in my brown backpack with my tax information and Illinois license plates, in the very back of the closet—is Nancy, my grandmother. She is framed, in a collared white shirt and a puffy blue-and-purple coat, smiling a slanted smile, with a koala curled in a tree beside her.

When I see her, I begin to cry, a kind of painful cry that hurts my face and comes from somewhere I haven’t visited in a long time. There is no resolution to this kind of cry, no words of consolation, nothing to solve. All there is to do is wait until it passes.

I didn’t know my grandmother, I cry, I wish I knew my grandmother. What I would give to know my grandmother. When my tears subside, I take the picture of Nancy and the koala into the living room and sit with it to write these words.

. .

It feels to me that each of us has a spirit. We must, right—there is something that connects us to the divine, even if our conception of what the divine is, is simply ‘love.’ I used to be more of the mind that our spirits are what make us who we are, but I don’t know anymore. I think who we are may be a composite of our minds, bodies, and spirits together. So then, if our spirit exists after death, it seems unlikely that it alone can be regarded as us—it is our bodies and minds who complete who we are. Here is where I want to adopt the Buddhist belief that there is “no self”—would that help with the crushing contemplation that we do indeed cease to exist upon our deaths?

In some moods, I find myself aligning with and nodding along to the writer Kathryn Schulz’ conception of death. Here is what she says of it:

“I have always regarded this to be one of the inviolable terms of our existence: the people we love cease to exist upon death, as definitively as water flows out of a glass when you overturn it.” (From Lost & Found.)

This is certainly not a flowery rendition of where we go after death. How could any of us know if that rendition is real? But I was not raised with a religious backdrop, and therefore my conceptualization of loss and death consists of ideas I try on for a while, and often discard without really believing that any of them are real. Spirituality has always felt to me like an exploration of possibilities, and not at all like finding any answers. I certainly don’t have any answers as to what happens after death, if anything. Still, that does not stop me from speaking to my grandmother, and to other people I love who have died, and considering that they are somehow listening.

Who really knows, right?

. .

In Kathryn Schulz’ memoir, Lost & Found, she chronicles, in an impossibly beautiful way, the coinciding of her father’s death with her lover’s arrival into her life. She draws the link between love and loss: they are inextricably intertwined.

Schulz says, astutely, that “The fundamental paradox of loss [is that] it never disappears.” This is the nature of grief, as well—I don’t think it will ever disappear. For as long as we love, we will also grieve. When we touch grief, we do so knowing that we will undoubtedly do so again. As the American Buddhist teacher Tara Brach speaks about, our grief often feels familiar: like it is coming from the same pool, regardless of what surrounds it. When you let yourself touch grief, even if the circumstances are foreign, the grief itself may feel familiar: as if you have known it, and been here, before. There is an element of universality to grief that all of us have access to. If we are connected by love, we must also be connected by grief. Some of us are more familiar with grief than others, and some of us know the pull of grief more personally. But all of us know it.

As Schulz reminds us, our lives, and the circumstances we find ourselves in, are transitory. Here, she speaks to the universality of loss and impermanence: “Sooner or later, it is in the nature of almost everything to vanish or perish. Over and over, loss calls on us to reckon with this universal impermanence—with the baffling, maddening, heartbreaking fact that something that was just here can be, all of a sudden, just gone.”

Does understanding impermanence help us grieve? Maybe. At the very least, it reminds us of our own temporariness—a fact of life that can serve to frighten or humble us. Knowing we are only here for a little while can encourage us to make the most of right now.

Still, understanding impermanence does little to curb the intensity of grief itself. I don’t think anything can really curb the intensity of grief itself—even substances that blunt our emotions can only work for a time. Grief will still be there when the high subsides. I have heard people say of grief, that as time passes, the pain does not hurt less, but it does hurt less often. This feels true.

. .

I call my mom an hour or so later after finding my grandmother’s poems. She tells me that her mom was always dating—she wanted to find the “right guy”. When I mention the love poem, she remembers David, who didn’t go to Australia with my grandmother, but was another man my grandmother dated, and who also was, apparently, the “right guy”. This makes me glad, to know that my grandmother found good love. It makes me sad, too, for her, and for David, wherever he may be. She loved a lot, in her shortened life. She loved, and lost, and grieved. And she left behind love, and loss, and grief in her wake.

I don’t think that we “have to” experience loss “in order to” learn something about life and love. That’s not a god I’d believe in. But, I do think that we can let our grief teach us. We can let the losses we experience show us the way forward; we can let them reveal to us what is important. We can let them open us up to the aching beauty of this world.

Can we let our hearts break open whenever they do, and show us how to continue?

Death is not the only great loss that can put us in contact with the universal pool of grief. Loss of any kind can invite us to touch that water. I think the important thing is to trust that we can touch grief, when it’s there. We can let it guide us and propel us into a deeper, richer understanding of life, and of love.

I lost my grandmother before I was born, and it has taken nearly 26 years for me to be open—and maybe mature—enough to touch the grief that her death has invited me into.

What is she teaching me, now? What am I learning from missing her, now?

To let it all in. To not be afraid of feeling what’s missing. I’m learning, again, that to love means to lose, and to lose means to love, and grieve, more deeply.

Happy Spring—may we all let grief pierce us as long as we can bear it, and see where it takes us.

Maggie

So your grandmother, a rose from the dead on easter Sunday. I find this whole idea very interesting